Voting is still open for Project Food Blog Round 9! To check out my entry & vote, click here.

"I knew I should have eaten something . . ." I muttered to myself as I stepped into Lecture Hall D at the Science Center at Harvard University. The room was filled with a warm and inviting aroma, the savory umami of kombu and stock. My stomach growled in protest.

Why would a lecture hall smell like soup?

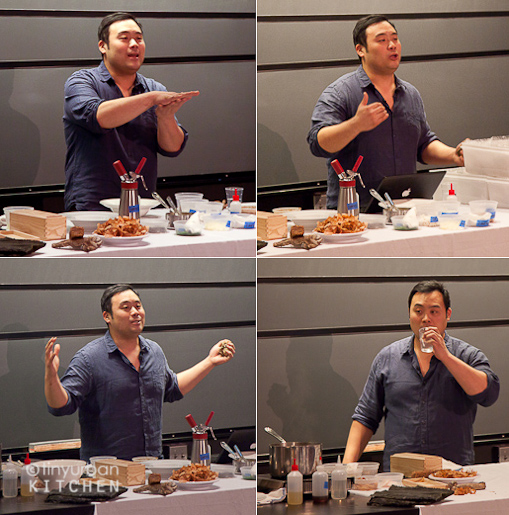

David Chang, from Momofuku, was giving the last lecture in the Science and Cooking Lecture Series at Harvard University. I had seen Wylie Dufresne's talk about meat glue several weeks back and loved it.

I couldn't wait to see what David Chang had in store for us.

He began by saying it was a crazy honor to be put in the same lecture series as the likes of José Andrés and Wylie Dufresne, who he says are really doing some cutting edge work in the field of food science. He really didn't feel like he was quite at the same level.

“I did terrible in science. I did terrible at school, which is why I became a cook.”

Instead of going for the next crazy innovative technique, "our goal is to try to find the next 'I wish I had thought of that.'"

Sometimes It Takes Desperate Times to Force True Innovation

Throughout the evening, David Chang brought up the same underlying message. True innovation often does not come until times get desperate.

In the early days of Ko (his first restaurant), they had a tiny 1600 square foot space in which to feed 300-350 people a day. “In order to serve that many people, that innovation was forced upon us.” They continued to learn by making mistakes and learning from those mistakes.

"Make a calculated mistake, make another mistake, one step backwards, three steps forward.” - David Chang

At Ssäm bar Bar, his second restaurant, he again highlighted his huge failures. He calls Ssäm bar his biggest failure yet.

"I had this great idea: let’s make Korean Mexican food!" Confident that it would be a hit with everyone, he took the mantra “If you build it they will come."

Nobody came. And things got desperate. The bank told them they had only 6 months to become profitable or else.

Forced under the wire, the Ssäm Bar team creatively attacked the problem "with a relentless tenacity" that they would not have had if everything hadn't "been on the line." The Ssäm Bar you see today is hardly the Korean Mexican restaurant that David Chang had envisioned. But it's OK, because that huge mistake and failure helped the team go above and beyond this "mistake" and become really, really successful.

“It takes discipline to write down your mistakes."

"All we do is screw things up. It’s been a progression of total disasters. It’s impossible to make cuisine, make something that is delicious without making mistakes.”

"And if anyone tells you they made delicious food without any mistakes . . . that's a bunch of bull$&#@" (the only profanity of the night!).

Apparently, 60 °C is the perfect temperature at which to cook kombu (kelp). It brings out as much umami as possible without extracting too many bitter compounds.

They pulverized the freeze fried meat into a powder and added it to the kombu broth. Unexpectedly, they realized they could make a pretty good broth with this method in under 45 minutes. They haven't released this to the restaurants yet (which still use the traditional 16 hour method), but he's really hoping to find a way someday to maximize efficiency in broth making, whether it be using this method or another.

Speaking of the Mushroom Sludge

At this point, he passed around a couple buckets of this interesting looking chip. This was another serendipitous discovery that came out of a need to solve a problem.

The problem? High quality shitake mushrooms are sold in large bins and take up a TON of storage space. The space at Ko was tiny. To save on storage space, they ground up the mushrooms into this "beautiful sludge" for storage. One day, someone tried laying the sludge out on a pan and drying it under vaccum.

The result? A beautiful shitake chip that, when seasoned with a little salt and spices, was an excellent bar snack. We all got to try a piece, and I agree that it was delicious!

The problem with Katsuobushi? The best stuff stays in Japan while only second-grade stuff is sent to America. And you need really good katsuobushi to make good ramen broth.

So how did David Chang get around this problem?

"In the US we have AWESOME bacon. We have jazz, country ham, baseball, and bacon. And that’s it. So why not take advantage of what we do well in America? Let's make our own 'bushi.' Let's make BACONBUSHI!!!"

They took pork tenderloin and applied the standard bushi-making method to it – they steamed it, smoked it over hickory, and dehydrated it. But what about the mold? He couldn't figure out how to get the right mold, so in an act of pure lazyness (or so he claims), he just threw the pork loin in a bucket of rice and stored it away for another day.

There was only one way to find out.

At this moment two people, Rachel and Ben, came up to talk about the research they had been doing on this piece of pork. They did "CSI-bushi" and analyzed the fungal and bacterial strains that were living in the pork.

He finished off the evening by showing us a cool foam-egg trick, his own spin on the traditional Japanese tamagoyaki. He squirted a foam of eggs into a pot of boiling dashi and then scooped it around a few times before forming this beautiful, airy egg blob.

They auctioned off Le Creuset dishware and the food he had just made but I didn't win. BOO!

All Rights Reserved

[…] of local projects, such as the insanely successful pop-up Guchi’s Midnight Ramen, the Harvard Science + Cooking series, and the Alícia Foundation. PAGU (which is the Japanese for pug), is located in the Takeda […]